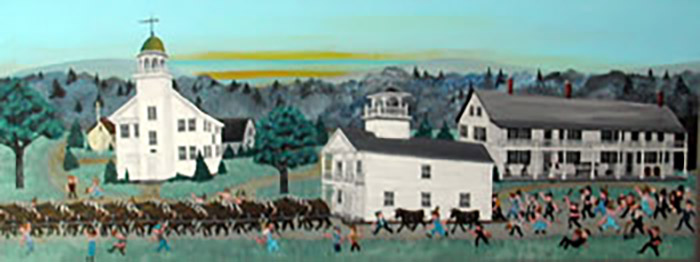

In the 1830s, tensions between supporters of slavery and abolitionists ran high all over the country. The small New England town of Canaan was no different. But here, in Canaan, there were residents who sacrificed their own money, reputation and safety in an attempt to provide higher education to young men and women regardless of race or color. The result of their earnest work was Noyes Academy, located next to the North Church on what we now call Canaan Street.

The Academy was named for Samuel Noyes, a Canaan farmer who first raised a significant amount of money to create the school which was located next to the North Church. George Kimball, Nathaniel Currier, and Nathaniel Peabody Rogers raised additional necessary funds to establish the school and then went further by lobbying the trustees to admit students of any color. The founders and trustees of the school believed all youth ought to have access to higher education. From the outset, it was understood that there needed to be a link between a college preparatory course of study, which the Noyes Academy offered, and admittance to a college for continued education. The location in Canaan for the school was due to its proximity to Dartmouth College, which had admitted African Americans by the early 1800s.

In July of 1834, Kimball, Currier, George Walworth and John H. Harris applied for and were granted a State charter for “the education of youth”. In September of that year the school trustees met and voted to allow students of all races to attend. It seemed that the first step toward equal opportunity education had been taken. Noyes Academy was the first upper level coed interracial school in the United States.

In late winter of 1835, black students began arriving at Noyes Academy. Once in Canaan, the students found families who welcomed them. A number of students lived with George Kimball’s family and at Nathaniel Currier’s house. There were 14 black students and 28 white students enrolled at Noyes.

In August 1834, when the school was first formed, some of the townspeople (perhaps 25% of the voters) objected to the idea of blacks being allowed to share a classroom with whites. Most of the town was supportive (or at least ambivalent to the idea) of the black students. The initial vote of the school’s incorporators was 49 in favor of offering integrated education and 2 against. At a meeting held later that summer, a vote of 70 residents, though, resulted in a motion opposing the integrated school or any school for blacks.

Editorials in widely available New Hampshire newspapers sowed fear in many in the community. There were three reasons given within New England for opposing the School. First, abolition of slavery would flood the labor market for work in the northern mills. The second reason was that it would encourage a civil war between the northern and southern states. A third was the belief that a school in Canaan created dangers of black men mixing with white women (after a black student and a white girl were seen walking arm-in-arm down the streets of Canaan) and the black students were known to interact socially with their hosts in the homes of abolitionists. This last argument was used by school opponents to create an emotional fear of the school in a community which had previously accepted the idea. While there were four or five hardened opponents, much of the ultimate violent opposition came from outside of Canaan.

Anti-abolitionist sentiment rose to a pitch on July 4, 1835, when a crowd of 70 men gathered in front of the school with torches, axes, clubs and a plan to destroy the school. Dr. Timothy Tilton, a town magistrate and trustee of the school, stepped between the school and the raging mob and threatened legal action if the men persisted in their violence. The protesters then arranged an official town meeting and took a vote, protecting themselves from legal action. A little more than 400 others, far in excess of the 300 total Canaan voters, joined the initial 70 protestors. Fueled by rum and passion, they returned to the school in full daylight on August 10, 1835 with oxen and chains.

Over two days they managed to move the building into the street and then dragged the school down the road to Canaan’s Meeting House where it was left as a splintered heap. The opponents included more than 100 volunteers from Enfield, Dorchester, Lyme and Hanover. Later, the Town’s legal counsel stated that the action of the demonstrators was illegal regardless of the town meeting vote, but the damage by the racist mob had been done. To quote Wallace’s history of Canaan, “There it stands, shattered, mutilated, inwardly beyond reparation almost, a monument of the folly of and infuriated malice of a basely deceived populace”. (Wallace, 1910)

The students were given hours to leave town. Several students Alexander Crummell, Henry Highland Garnet and Thomas Sydney, went directly to the Oneida Institute, near Utica, NY, where they were welcome. Although a school for men, Oneida Institute also accepted Julia Williams, one of the few black women who also attended Noyes. These individuals are known to us now because of their work in the abolitionist movement.

Three years later the remains of the school building was set on fire and burnt to the ground.

In 1839, the Union Academy (now home to Canaan’s Historical Museum) was built across from the Meeting House. Though styled after Noyes Academy in appearance, the new school was not integrated.

Noyes Academy wasn’t the only abolitionist activity in the town of Canaan., Years prior to Noyes Academy. at least three homes in town were known stops on the Underground Railroad, the tangled system of paths, hiding places and supporters for fleeing slaves on their dangerous journey to Canada. These included the Currier House on Canaan Street and George Kimball’s house (known as Twin Gables) on Prospect Hill Road. James Furbur, who lived across from the Kimball’s, hid escaping slaves in his large barns.

A number of students from the academy won deserved prominence as adults.

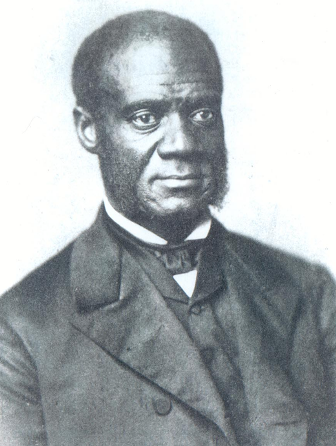

*Thomas Paul was one of the earliest black graduates of Dartmouth. He became a prominent Baptist minister who tied biblical teachings to social justice and the quest for equal acceptance of African American in society.

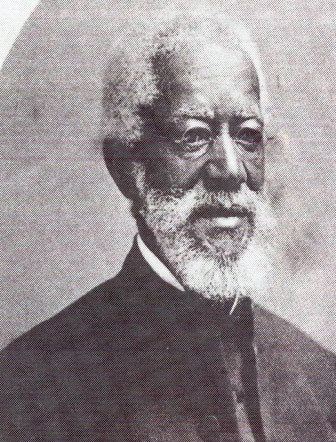

*Henry Highland Garnet continued his education at Oneida Institute and became a minister and abolitionist leader. He married Julia Williams, also an abolitionist and fellow student of Noyes Academy. He made an invited speech in the U.S. House of Representatives before being appointed ambassador to Liberia.

*Alexander Crummel became a pioneering Episcopalian priest. He lectured against slavery in England and studied for three years at Cambridge University, developing a movement supporting bonding in solidarity between all indigenous and diaspora people of African descent.

*Following his time at Noyes Academy, Thomas Sydney, a founder of the Philomathean Society, attended the Oneida Institute where he was distinguished for his scholarship.

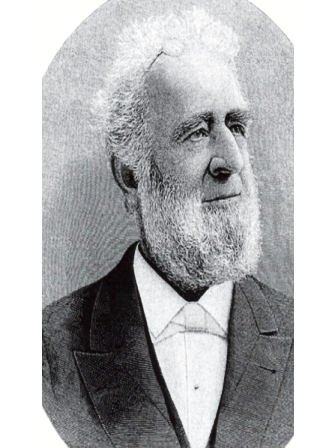

*Rev. Richard S. Rust, DD, of the Methodist Episcopal Church, was a white student who later helped found Wilberforce University, a college whose mission was to help educate former slaves. He worked to establish as many as 30 other colleges and institutions, mainly for teachers, with the idea of educating former slaves and their children.

“There are lessons to be learned from Noyes. My first observation is that there were many members of the Canaan community in 1835 that cared passionately about racial and gender equality and invested their time and money to make equality a reality.

The second is that fear of the unknown, (especially when stoked by false or misleading statements) can turn law-abiding citizens into an angry mob”.